Jenny Jump for Your Love

May. 2nd, 2021 03:10 pm

I haven't written here in about four months. My general rule is that I use this for posts that are more of a run-down of things I've done than examinations of a subject, although it's sometimes difficult to make the distinction. The thing is, I haven't done much worth talking about in the recent past. Yesterday, however, was an exception. John R. Neill's introduction to The Wonder City of Oz, the first Oz book he wrote as well as illustrated, says, "We live on the top of the Schooley Mountains and the Jenny Jump Mountains are really truly mountains right next to us. They are wonderful mountains for fairies to hide in." So I decided Beth and I should visit both places, as they're not that incredibly far away. We'd been meaning to go for a few weeks, but we'd had to put it off because of a recall on my car. But now the car has been deemed okay, so we made the trek yesterday. On the way, we stopped to eat at Panera Bread. I hadn't been to one since we lived in Secaucus, and I was annoyed by those commercials they had that referred to "clean food," as if every other restaurant serves filth. I mean, some do, but I figured that was the minority. But it's really not fair to let bad advertising sour me on something. I wouldn't have drunk Red Bull even if they didn't have those painfully unfunny ads. But anyway, Panera is one of those places where they don't tell you on the menu everything that's in each sandwich, which is frustrating when you're a picky eater. But they do now have flatbread pizzas, and the one I had was good.

I read online that the house Neill lived in from 1936 until his death in 1943 was at 94 Tinc Road in Flanders, New Jersey. That's a very narrow, windy road; but fortunately there's a sidewalk along the relevant part.

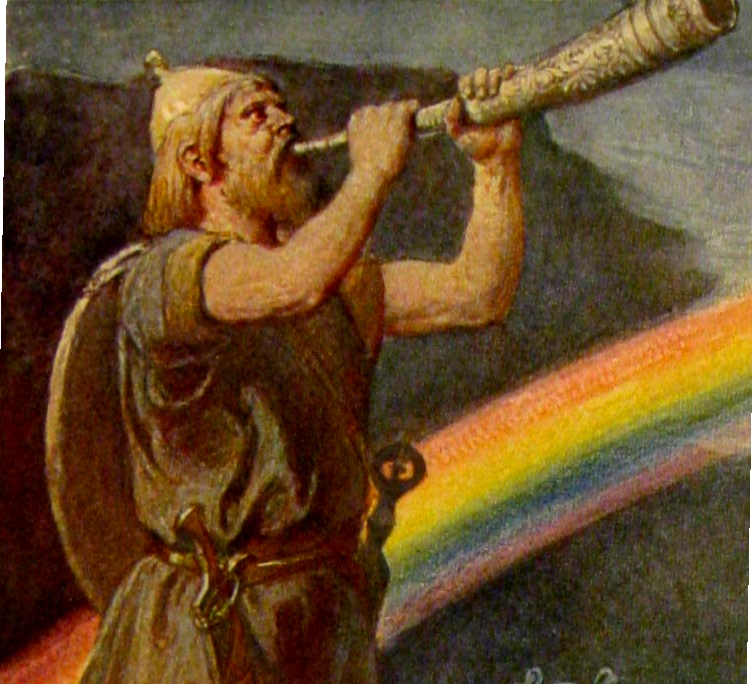

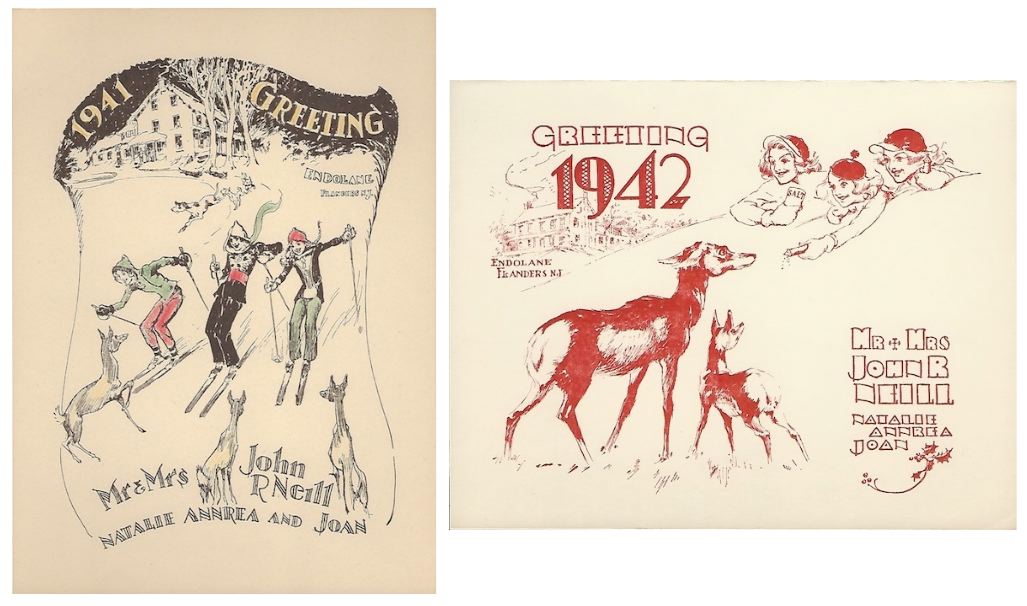

I wasn't sure whether the same house was still there, but this drawing from Neill's 1941 Christmas card definitely looks the same as the one I photographed.

Picture source: Bill Campbell's Oz Enthusiast blog

I don't think the property is as big now as what the illustrator owned, though. Neill called the place Endolane, but I have no evidence that this name is still in use. When I looked at the Endolane tag on Instagram, most of it was for a farm in Rhode Island. The street that branches off from Tinc Road right near there is called Neill Lane after him.

It's spelled with only one L on this sign, but it kind of looks like they just ran out of room. Perhaps this is the lane with the farm at the end o' it that Neill's name referred to, but I can't say I have any idea what the street layout was all those decades ago. I've seen Ruth Plumly Thompson's house in Philadelphia before, and I don't think any of the places L. Frank Baum lived are still standing.

Jenny Jump is a state forest in the mountains with an address in Hope Township. Some sources I looked at say that there's one particular Jenny Jump Mountain, but I don't know which one this is. There are several trails through the forest. We walked the Swamp Trail (although neither of us saw a swamp) and then tried the Spring Trail, but when we realized there was a very steep, narrow, rocky incline not far from where it started, we gave up.

We then drove to the ominously named Ghost Lake on the even more ominous Shades of Death Road.

I can't say the part we drove on had any noticeable shades of death, although it did have a big sod farm. The scariest thing I saw in the area were Trump signs and those thin blue line flags. I'd seen those flags for some time before I knew what they were for, but even then they looked dystopian. Even putting aside the racism, why would anyone want to advocate for a police state? I guess it's not a surprise that a rural area would be largely Republican, which isn't to say that it makes sense. And it's not like I don't see some of that same stuff in Brooklyn. Anyway, Google Maps showed a place called Faery Cave next to the lake, but we couldn't find how to get there. According to the comments, the trail is pretty overgrown, and it's not really that interesting anyway. But it does bring to mind Neill's comment about fairies hiding in those mountains. I wonder if the cave had the same name back in his time. I didn't see any leprechauns there either.

In other news, I'd been going to the office two days a week, and working from home on the others. Starting next week, I'm going to be in the office three days every other week. I liked working from home, but my office was so reluctant to do that in the first place that I'm not surprised they're phasing it out as soon as possible. It's not even being in the office that bothers me so much as the necessary preparation and getting up an hour earlier. I also wish they'd waited until masks were no longer recommended indoors. Yeah, I know there are jobs that always require masks, but I'm not used to it, you know?