Who wrote the Bible? This is a question that's been debated considerably over the centuries and millennia, and there's plenty of information online and elsewhere supporting different views. Since it's a topic that interests me, I intend to devote a few posts to it, despite the fact that I doubt I'll be saying anything new. To many, the authorship is a moot point, because God wrote the whole thing. Why God would work in so many different styles and espouse different philosophies isn't clear, but that's another issue. Others believe that the Bible was simply inspired by God, or that it was entirely the work of humans. Not surprisingly, I take the latter view. Whether or not the Almighty was at the helm, however, the books were obviously written down by different people.

The first five books, known as the Torah or Pentateuch, have long been considered to be the work of Moses. The thing is, however, that even if you accept those books word for word, nowhere in there is there an indication that Moses wrote them. He's said to have written various things, but not those entire books. And how would he have written about his own death, which is recorded at the end of Deuteronomy? Indeed, it isn't even written as if someone just added this part shortly after Moses' death, as the final chapter of Deuteronomy implies it had been some time since then. It's reported that no one knows Moses' burial place "to this day," and that no other prophet as great as Moses has arisen since, neither of which would have made much sense unless a considerable amount of time had passed. So how did the tradition of Mosaic authorship develop? Really, it's so old that I don't think we can determine the true answer, but Wikipedia indicates that both Josephus and Philo proposed it during Roman times. It's more likely that the books were the work of several different authors, and the

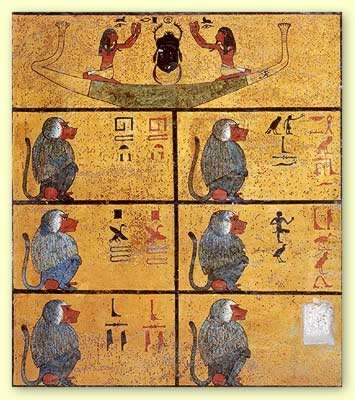

Documentary Hypothesis proposes at least four original documents that were combined to make what we now know as the Torah. Among the differences between these authors were what they called God (Yahweh vs. Elohim), which of the two Jewish kingdoms they supported, and whether they focused on Moses or his brother Aaron. The book of Deuteronomy has a particularly interesting history, as it is typically identified as the scroll found in the temple during the reign of Josiah of Judah. Skeptics suggest that it might have actually been written in Josiah's time, with the priests successfully managing to pass it off as the work of Moses.

/images/scan0029.jpg)

Moving on to Joshua, this account of the conquest of Canaan is also credited to its main character, Joshua himself. Archaeological evidence has cast a considerable amount of doubt on the idea that the conquest was accomplished in such a neat fashion in a short amount of time, which suggests that Joshua either didn't write it or was exaggerating his own accomplishments. The book also reports the death of its protagonist, with Aaron's son or grandson traditionally identified as the one who wrote this part. I tend to think that even that is pushing it, however, due partially to more "to this day" references (see the story of the twelve stones in Joshua 4, for instance), and also to the mention of the mysterious Book of Jasher in Chapter 10. This book, the title of which literally means "Book of the Upright/Just," has never been found, despite claims that were later found to be forgeries. And this isn't its only mention in the Bible, as 2 Samuel 1:17-18 says, "David intoned this lamentation over Saul and his son Jonathan. (He ordered that The Song of the Bow be taught to the people of Judah; it is written in the Book of Jashar.)" This is from the New Revised Standard Version, and other translations make it less clear exactly what was recorded in Jasher. If it's the song that immediately follows, however, it mentions Saul and Jonathan by name, and hence couldn't very well have dated back to the time of Joshua. Maybe there was more than one book with that name (I've seen indications that Genesis was sometimes known by that title, although it obviously isn't Genesis being referenced in either of these cases), or it was updated like an almanac. If we do consider the two books to be the same, though, it means that Joshua as we know it couldn't have been finished until after the death of Saul. As with the Torah, that doesn't mean that parts of it might not date back to eyewitness accounts, but we're obviously looking at a document that had undergone at least some revisions. As for the attribution to Joshua, could he even write? I'm not being flippant here, but merely pointing out that the Biblical account has Moses raised as a prince and Joshua as a slave, so there presumably would have been a significant difference in educational level between the two.

Thankfully, it doesn't look like anyone has tried to attribute the book of Ruth to its main character. Instead, the traditional view holds that it was written by Samuel, as were significant portions of Judges and 1 Samuel. It would make a certain amount of sense for Samuel to have popularized the story of Ruth, as he was promoting Ruth's great-grandson David as the next King of Israel. On the other hand, the story indicates that David was of Moabite ancestry, which might not have gone over too well. As for the books of Samuel, 1 Samuel 9:9 explains how prophets used to be called seers, while 10:12 explains the origin of the expression, "Is Saul among the prophets?" Both of these would presumably have been unnecessary if the book had been written by a contemporary of Saul. And Samuel is dead by the beginning of 2 Samuel, which not only means that he couldn't have written the book, but that whoever came up with its current name was quite likely an idiot. I know some versions of the Bible group the books of Samuel and Kings together and call them 1-4 Kings, which really makes more sense.

Collectively, the books of Joshua through 2 Kings (not counting Ruth, which appears later in the Tanakh) are known as the Deuteronomistic History, due to their views and concerns being similar to those in Deuteronomy. The kings and people are judged by how closely they conform to the laws put forth in the last book of the Torah. Some scholars have proposed that the compiler (and perhaps even writer) of these books was Jeremiah. Not only is the style similar to that of the book of Jeremiah, but this prophet was also known for blaming the hardships of the Jews on the deeds of the kings and their people. The reports of the kings are given from a specific viewpoint, and most are not intended to be complete (the accounts of Saul, David, and Solomon perhaps being exceptions). Indeed, the books of Kings constantly refer to the Annals of the Kings of Israel and Judah, which were presumably much more detailed sources. Unfortunately, these Annals have been long since lost to history.

If there's any interest, I'll continue this series in later weeks. Until then, you can read more about the topic

here and

here.

/images/scan0029.jpg)